John Bombaro: In God’s Two Words you bring Lutherans and Reformed into conversation on the distinction between law and gospel. What is it about this topic that compelled you to choose it as a conversation piece for today?

Jonathan Linebaugh: In the sixteenth century, the Protestant reformers both had wanted to have this kind of conversation. Perhaps the most well known instance is the Marburg Colloquy (1529), a meeting at which leading reformers were able to agree on a range of essentials of the evangelical faith. This event, however, is remembered more for the one place they couldn’t agree: the Lord’s Supper. Because of this continued disagreement, many wanted to continue the conversation. Thomas Cranmer, for instance, invited Reformed and Lutheran theologians (Phillip Melanchthon and John Calvin among them) to England. But that meeting never happened, and so, in a sense, the invitation to this kind of interaction and exchange still stands. This book is an attempt to pick up, join in, and continue a conversation that began in the sixteenth century but is far from finished in the twenty-first.

The distinction between law and gospel is fundamental to both Lutheran and Reformed theology. Just as Luther says, “Anyone who can properly distinguish the gospel from the law may thank God and know that he is a theologian”, so similar quotes flow from the Reformed: “the gospel differs from the law” (John Calvin) and “We divide the word into two principal parts or kinds: the one is called ‘law’, the other the ‘gospel’ (Theodore Beza). But that doesn’t mean the Lutheran and Reformed understanding of this shared distinction has always been the same. The Reformed theologian Herrmann Bavinck, for example, can note the commonality—“the word of God [is] both law and gospel”—and then say that the Lutherans and the Reformed have “a very different view.” In the twentieth century, Lutheran theologians (provoked by Karl Barth but still talking about the Reformed tradition more generally) could critique Calvin’s understanding of law and gospel (Werner Elert) and identify a “difference between the Lutherans and the Reformed” (Hermann Sasse).

There is, however, another and deeper reason for talking about the distinction between law and gospel. In Calvin’s words, this distinction “can extricate us from many difficulties” because it reveals “that the righteousness which is given us through the gospel has been freed of all conditions of the law.” The hope from which this book was born was a shared sense that the distinction touches something fundamental for Christian faith, that it matters for ministry, that it informs and impacts preaching and pastoral care, and that it describes the way God acts through his word to “kill and make alive” (1 Samuel 2:6), to “imprison all in disobedience so that he might have mercy on all” (Romans 11:32).

John Bombaro: The Reformation understanding of the authority of Scripture (sola Scriptura) includes Scripture’s in-built hermeneutic (i.e., how the Bible directs us to read it). How do the traditions of the Reformation understand the authority and interpretation of Scripture?

Jonathan Linebaugh: Both Reformed and Lutheran traditions confess that Holy Scripture is God’s word, that it is, as 2 Timothy 3:16 has it, “breathed out by God.” Combining this confession that Scripture is God speaking with another, the reformers insisted that God’s word is true—God does not lie (Numbers 23:19).

To say Scripture is God speaking, however, is also to say, “the Word of God is living and active” (Hebrews 4:12). Throughout Scripture, God acts by speaking: “Let there be light,” “Little girl, get up,” “Lazarus, come out.” As Psalm 33:9 says, “He spoke, and it came to be.” The God who cannot lie is also and ever the God whose word says what it does and does what it says. For the reformers, then, to talk about the authority of Scripture is to say Scripture, as the word of God, is both true and powerful.

Luther emphasized this latter point with the phrase, “Scripture is its own interpreter.” This suggests that Scripture speaks the kind of word God speaks when he calls the creation into being and calls the dead to life. Scripture is not just words waiting for an interpreter to make sense of them; Scripture is God speaking and God speaking is God acting. It is, in other words, not so much we who interpret Scripture; it is God who through his word interprets us.

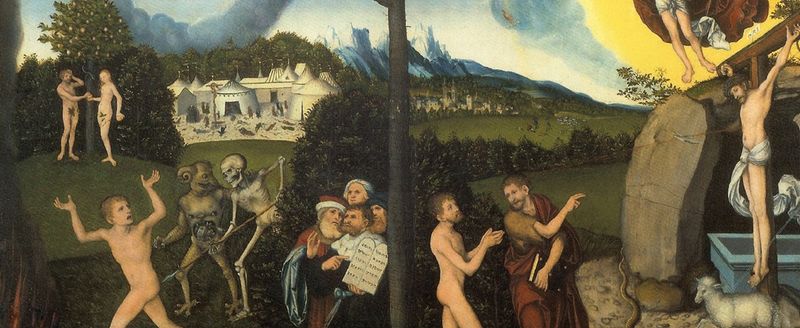

The distinction between law and gospel is a way of describing what God does to those to whom he speaks. God has business with the Old Adam and Old Eve: to show them their sin and to kill them as sinners. God also has business at the graveside: to forgive, call righteous, and so resurrect new creatures of faith who are God’s beloved children. God does these two works through two words: He speaks diagnosis and death through the law; He speaks liberation and life through the gospel. Law and gospel, in other words, are not a strategy or technique for reading the Bible; they are not first categories by which we index and interpret God’s word. Rather, law and gospel name the actions of the “living and active word” by which God interprets us, the words that work our diagnosis and death and then work our redemption and resurrection. One way to capture this is to look at the image on the cover of the book. It’s one of several pieces Lucas Cranach the Elder crafted to convey the distinction between law and gospel. It’s possible to see and interpret it is as a kind of how-to for hermeneutics and homiletics, a map of sorts for reading and preaching Scripture: when you find things in the Bible like the Decalogue and the final judgment, interpret and proclaim them so that by reading you and your hearers run into the flames of condemnation and death; then, when you find things like the cross and empty tomb, interpret and proclaim them so that by reading you and your hearers run to the lamb that takes away the sins of the world. The distinction between law and gospel is, of course, a rich and remarkable help for hermeneutics and homiletics, but not because it lets us categorize and control Scripture. An image like Cranach’s, in which the human figure is passive and undergoing the action of God’s word, reminds us that while the distinction between law and gospel provides direction for reading and preaching, it does so because it is more fundamentally a description of what God will do to you and for you as he speaks in Scripture. God’s word, as George Herbert once wrote, is the “well that washes what it shows.” It is the word that shows us our sin and the word that washes away our sin, the word that shows us our “thirst for righteousness” (Matt 5:6) and the word that gives us living water from the well of “Christ, who is our righteousness” (1 Cor 1:30).

John Bombaro: How might a volume like this benefit Christians in their understanding what God says and also how He uses His “two words” of law and gospel?

Jonathan Linebaugh: As creatures we are fundamentally hearers and receivers. Scripture is God speaking and acting. Reading Scripture is being addressed and acted upon. Reading is receiving and only then responding in faith and love. This is the proper position and posture, not just for encountering Scripture, but also as creatures and children of our creator and heavenly Father.

What I want to stress most, however, is that, to quote an early English evangelical document, “there is nothing more comfortable for a troubled conscience than to be instructed in the difference between the law and the gospel.” Luther remembered that it was “when I realized the law was one thing, and that the gospel was another, I broke through and was free.” This comfort doesn’t come from understanding this distinction “at the level of words.” At that level, Luther felt “there is no one so stupid that he does not recognize how definite this distinction” is. “So far as practice, life and application are concerned,” however, so far as we are talking about actually trusting in moments of temptation, sin, suffering, and death that God relates to us not on the basis of our observance of the law but on the basis of the life, death, and risen life of his Son, this distinction “is the most difficult thing in the world.” The distinction between law and gospel, in the end, is not a human act but a divine art, an art that, as Luther wrote, “Only the Holy Spirit knows.”

The distinction between law and gospel is not “comfortable” because it puts us in control. It is “comfortable” because it frees us to be creatures, those who live by every word that comes from the mouth of God (Matthew 4:4). It is ultimately God, in the power of the Spirit, who speaks what Luther calls “the sermon which we should daily study… In it both imprisonment and redemption, sin and forgiveness, wrath and grace, death and life are shown to us… The first thing about sin and death is taught us by the law, the second about redemption, righteousness and life by the gospel of Christ… One must preach the law so that people come to a knowledge of their sins… One should preach the gospel so that one comes to a knowledge of Christ and his benefits.” This isn’t just Luther, however. The Reformed theologian William Perkins writes, “when the word is preached the law and the gospel operate differently… The law exposes the disease of sin…but provides no remedy for it… By contrast, a statement of the gospel…speaks of Christ and his benefits.”

It is this sermon in the Spirit, this divine art—God’s two words—that is “comfortable for troubled consciences,” that makes “bruised bones leap for joy” (Thomas Bilney), that answers the cry “Is there any comfort—any hope” (George Eliot) with the finger of John the Baptist that points to and proclaims, “Behold the Lamb of God that takes away the sins of the world.” God’s law shows that God knows us in our sin, shame, secrets, and suffering: it is a word that diagnoses the dead. But God’s gospel is announced at the graveside and it shows that we who are known and dead are finally loved and given life. The law is not advice for the Old Adam, a form of life-support for sinners. Spoken to the Old Adam and the Old Eve, the law is not about repair; it is God’s first requiem, a funeral sermon that’s followed by a final sermon, the gospel requiem that resurrects. To quote that English evangelical text once more, “The law shows our condemnation; the gospel shows our redemption. The law is a word of despair; the gospel is a word of comfort… The law says where is your righteousness? The gospel says Christ is your righteousness.”

What God sees and says when he looks at you—your being enough and being loved—is not determined by what you have or haven’t done; it is determined by what God says to you, by what God has done, is doing, and will do for you in Jesus Christ. This, as Thomas Cranmer called it, is the “comfortable word.” This distinction frees us from the inhuman quest of using the law and our works to secure our standing before God and frees us for the human life of receiving from God and responding with faith in him and love for others. The “do” of the law is distinguished from the “done” of the gospel, and the law’s “if” gives way to Jesus’ “It is finished”—the three words that speak the final three words God says to sinners in the gospel: “I love you.”

John Bombaro: The Lutheran emphasis on solus Christus (Christ alone) sounds to some like embracing a gospel-reductionism that compromises the third use of the law. Is this an obstacle to Lutheran-Reformed dialog?

Jonathan Linebaugh: The Reformed champion the solus Christus as clearly and uncompromisingly as the Lutherans. And while there is internal Lutheran debate about the “third use of the law,” it is part of the Lutheran confessional tradition (the phrase was coined by Phillip Melanchthon). That said, the third use of the law is a way into some of the differences between the Lutheran and Reformed understanding of the distinction between law and gospel. Although Luther himself spoke of a two-fold use of the law, both the Lutheran and Reformed confessions affirm a threefold use of the law: a political use (to restrain sin), a theological use (to reveal sin), and a third use (a use of the law for Christians). According to Bavinck, however just here the Lutheran and Reformed have “a very different view.” Both traditions insist that the law as well as the gospel must always be preached to Christians. (That means they both affirm the third use and so reject antinomianism.) For Lutherans, however, this is necessary insofar as Christians are still in the flesh and so, in themselves, sinners. For the Reformed, the law is for the Christian both as they are in the flesh and in the Spirit. “The law,” writes Calvin, “which among sinners can engender nothing by death, ought among the saints to have a better and more excellent use.” This aligns with Calvin’s use and reapplication of some of Luther’s language: whereas Luther called God’s use of the law to reveal sin and condemn sinners the “primary purpose” and “chief and proper use” of the law, for Calvin the third use is the “principal use” and “pertains more closely to the proper purpose of the law.” The question is whether God’s good law is only for the world as fallen and thus the person as a sinner, or whether the law is originally (and principally) for the world as created and thus the person as redeemed.

This difference may open a door onto more and deeper differences: Can law and gospel be held together in a more basic category like covenant or are they, for “the theology we do as pilgrims” (Oswald Bayer), irreducibly distinct? Is the scope of theology as wide as “the knowledge of God and of ourselves” (Calvin) or more narrowly “the human being accused of sin and lost, and God, the one who justifies and rescues the sinful human being” (Luther)? Are law and gospel both part of Christ’s real work, or, as Hermann Sasse expressed the Lutheran view, is “the preaching of the law the ‘strange’, and the preaching of the gospel the ‘real’, work of Christ”?

Despite these differences the distinction between law and gospel is fundamental to the Reformed and Lutheran traditions. Both insist that God’s word is law and gospel. Both insist that through the law God works to restrain and reveal sin. Both insist that the law needs to be preached to Christians as the word by which God works to continue restraining and revealing sin and also as the word that resists self-chosen works as it gives form to Christian freedom in worship of God and love of others. And, crucially, while affirming that the law is God’s, that it is holy, righteous, and good, and that through it God works, both traditions insist that the law is not the gospel. The law that curbs sin and condemns sinners cannot forgive sin or resurrect sinners. That work—of forgiveness and creating faith, of liberation and life, of redemption and resurrection—is the work of God through the word of the gospel. The distinction between law and gospel, in other words, is not about reducing God’s word and work to the gospel. The law is good, but the law is not the gospel. God speaks both words and by speaking each word God works. This is not a “gospel reductionism.” This is a distinction between law and gospel, a distinction that serves the declaration of both law and gospel, and a distinction that insists that the God who speaks his word of law is the God whose final word is the gospel: “You are my beloved son, you are my beloved daughter, in you I am well pleased.”

John Bombaro (Ph.D.) is a Programs Manager at the USMC Headquarters. He lives in Virginia with his wife and children.

Jonathan A. Linebaugh is Lecturer in New Testament in the Faculty of Divinity at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Jesus College. He is the author of God’s Two Words: Law and Gospel In Lutheran and Reformed Traditions, the subject of this interview, as well as God, Grace, and Righteousness in the Wisdom of Solomon and Paul’s Letter to Romans and co-editor of Reformation Readings of Paul.

Editors Note: This interview with Dr. Jonathan Linebaugh was originally published at MR on Feb. 6, 2019.