After 25 years of working in the art world, I remain fascinated by the sheer absurdity and vulnerability of a life devoting to loading a paint brush with smelly, messy pigments and smearing them along a scrap of canvas with the belief and hope that it will become more than the sum of its materials and address a viewer in a powerful way. With so much more relevant, socially-useful, financially stable, and more respectable professions available, why paint? I continue to think about that question and the shocking asymmetrical reality wherein in that the artist kills herself, pouring herself into that body of work that she, by hook or crook, presents to a public, and for a public who uses it as entertainment; to get a bit of “culture,”, or just an excuse to meet friends and enjoy free wine and cheese. But that artist is making that work, not necessarily for those people or for the collectors who keep the lights on in her studio and pay her kid’s childcare bill, but for a heart that is open and ready to receive something else. The painter Edvard Munch (the painter of The Scream (1893)), wrote in his journals that he paints his ‘soul’s diary’; that he paints to find order, clarity, and truth in his life and in the world. He hoped that his paintings might help those who encountered them in their own search for clarity, truth, and understanding. That is the covenant of modern art.

How does the vocation of artist reveal something about all of our vocations? How is it that the oddity and peculiarity of the artist’s life gives us a new view of our own work; of who we are as sons and daughters of Cain? There is too much superficial romanticizing, glamorizing, or stigmatizing the life and work of artists; too much exaggeration of their self-expressive “creativity” and “freedom” that obscures the deeper fundamental aspects of what it means to devote one’s life to a practice that is never self-evident, always in need of justification, and seems irrelevant, absurd, self-indulgent, and useless in the modern world. I’m not trying to convert people to “modern art”, but to show how a particularly obscure creative cultural practice might reveal something insightful about the gospel and about human life as it’s lived in all its robust emotional range of fear, regret, hope, anger, faith, and unbelief.

Modern Art Is (Generally) More Theologically Realistic

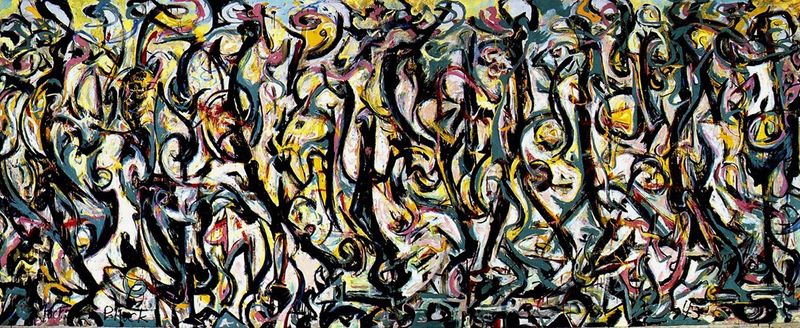

Modern art operates in a register akin to the theology of the cross, which Luther contrasted sharply with the various theologies of glory that he felt defined the Roman Church. In many ways, the great Renaissance painters like Raphael and Michelangelo (and the classical tradition that developed from them), are theologians of glory, presenting us with the saints, gods, goddesses, and heroes whose heroism, martyrdom, and triumphs present us with virtuous models to imitate. While the Renaissance and classical painter illustrated theology, the modern artist, stripped of the certainties and stabilities of the Church (not to mention the commissions to paint as part of the liturgical context of the Church), paints theology; that is, they use the practice of painting to ask the fundamental questions, “Who am I? Where did I come from? Where am I going?” These paintings aren’t part of the Church’s public, communal affirmation of a dogma visualized or made visible, but are visual, tangible articulations of questions that enter secular homes, secular spaces, often in search of the viewer who can hear its deeper call. The awkward, clunky, and strange-looking works of the modern period operate as aesthetic theologies of the cross; painted theologies that declare our vulnerability, fragility, and a life lived as wanderers east of Eden—not pictures of the glory to come and the beauty to which we aspire. They’re not always intended to inspire or elevate, but through their vulnerability, weakness, and fear, they give us glimpses or intuitions of God’s grace. But they require the viewer to first look beyond the obvious, and second, to be receptive to whatever that painting may make them think or feel.

Modern art is a kind of ‘preaching-in-paint’; a preaching of both law and gospel. The history of modern art is a history of artists lamenting their fear, anger, and disillusionment in the face of an unjust world. Like the prophet Jeremiah in the book of Lamentations, David in his Psalms, and Job, artists don’t ignore those fears and emotions and expressions of putting God on trial. They paint them. They are not afraid to express their anger and confusion. The visual arts have been and continue to be used as propaganda for the virtuous life, the heroic life, etc., and as encouragement for struggling pilgrims, they do well enough. But there is an important tradition in modern art that reminds us that we are born of dust, and to dust we will return. We are vulnerable, fragile, and suffering creatures. This dose of reality takes us to the brink of meaninglessness, to nihilism, which is a secular preaching of the law. But that is rarely the last word in modern art, for it is in this hopeless, bleak landscape of meaninglessness and senseless suffering that glimpses of light and the subtle breeze of grace and hope begin to be seen, felt, and heard. They hint at the reality of the gospel, a sense that there is something Beyond, even though that may not have been the artist’s intention.

Modern Art Is About Truth, Not Affirmation

Most of what we know about art comes from social media and thus through “news” that focuses on scandal and absurdity; the news that always puts modern and contemporary art on the defensive. Moreover, it is precisely in this register of confirming what we already know, entertainment, and other forms of utilitarian knowledge and entertainment that obscures the truth of art.

What makes painting so interesting is that it uses our most superficial and judgmental organ—our eyesight—and asks us to look beyond the color and shape and size; to not be deceived by what we see. That visual discipline has to be preserved in the experience of art in the age of Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. An artist doesn’t make a work of art to be glanced while we absentmindedly walk by or scroll through our Instagram feed. It requires us to stop in front of it and allow the painting to make the first move, so that our response is a thoughtful engagement (or even what Luther called a “passive” one) instead of an instinctive reaction. Remember that in the New Testament, seeing is not believing; rather, it is sight that is pitted against belief (John 20:27-29). But art is primarily a visible medium—how does that jive with faith coming through hearing? It does so by giving us something beyond the visible; something through which we experience the world that pushes back against our human tendency to reduce it to a visual (i.e., controllable) object.[1]

Ultimately, what confuses all of us about modern art is that it seems to contradict what we think art is about, which is rendering “realistic” representations of the world as we already know it. Modern art reveals that the visual arts have always been about that ‘something more’ or ‘something other’ that cannot be reduced to brute fact. It’s that ambiguity—and, by extension, all non-conceptual supra-rational knowledge about the world that can’t be quantified—that is so intimidating to us. It’s a cultural practice with a tradition that takes time and effort to learn. It’s like C. S. Lewis’s description of the liturgy as a learning to dance—it’s awkward at first, but we have make the effort to learn it in order to be able to express ourselves through it. We’re born with the inclination to worship, but we’re not born knowing how to worship. Similarly, we’re born with the urge to create, but it takes time to learn how to hone and refine that urge into an ability to engage with the creation itself with fluency and grace.

Modern Art Is Uncomfortable

We’re not comfortable with the world that modern art presents to us—it confronts us as a question (not a discrete set of neatly ordered categories) and undercuts what we think we know about art, and by extension, the world. It strips away all the cultural identities we adopt and reveals us as the sexless, child-like figure of Edvard Munch’s Scream, standing on that bridge experiencing the silent howl of human anger, confusion, helplessness—a howl that can only take an extra drink or two, a bad grade on a test, or someone cutting you off in traffic to release. We, as the old Adam, invent all kinds of ways to shield ourselves from that reality. It is that existential situation (which Bultmann, Ebeling, Tillich, Barth, and other modern theologians emphasized) that American Christians refuse to acknowledge. It is only in confronting and silencing the old Adam, if only for a moment, that we experience the comfort and joy of the gospel. Life is not a prison sentence, but it is a gift given freely by a God who is for and not against us. But we have to honestly acknowledge the darkness, ugliness, and evil that exists not only in the world but also in us before we can truly give good thanks and glory to the Father for it. For some people, the tradition of modern art offers something like that preaching of Law that kills—it exposes our own vulnerability, weakness, and dependence; our inability to provide a pat answer for every situation and circumstance—while for others, these paintings evoke the experience of faith, hope, and love, by allowing the viewer to see past the pigment and brushstroke to the transcendent reality they point to.

Daniel A. Siedell is an art historian and educator. He was the Chief Curator of the Sheldon Museum of Art at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (1996-2007) and presently serves as the Senior Fellow of Modern Art History, Theory, and Criticism at The King’s College in New York City. He is the author of God in the Gallery: A Christian Embrace of Modern Art and Who’s Afraid of Modern Art? Essays on Modern Art and Theology in Conversation.

[1] For more on this concept and its relation to the theology and tradition of the icon in the Eastern Orthodox Church, see my God in the Gallery.

This article was originally published by Modern Reformation on October 29, 2018.